-

On The Refugee Route Part III: Smuggling - An Act Of ...

On The Refugee Route Part III: Smuggling - An Act Of Resistance

It had been more than three weeks since Somar and his sisters commenced their long journey. Although they had not yet touched European soil, not a day had passed without them fantasizing about their parents one day following them to Germany.

The impossibility of safe and legal entry into Europe had accentuated their frustration, and an overburdened Somar began to attach a degree of legitimacy to the process of getting smuggled. After all, the states immediately affected by the Syria crisis each appeared to be neglecting their humanitarian obligations in some way. His home village had been under siege for months, there were rumours that host countries had closed their borders to asylum seekers, and Turkey’s ‘deals’ with Europe to stem the flow of Syrians into Europe sat uncomfortably with the many smuggler groups ready and willing to transport groups to the adjacent continent.

While political power-holders ogled to assert control over the situation, it seemed that the weight of morality had been thrown at the hunched backs of those walking on foot towards a more dignified life. The hypocrisy was overwhelming.

It was against this backdrop that a culture of resistance fostered among Somar, his sisters and their friends. And perhaps such feelings softened their trepidation. “If you believe in something so dearly and work cautiously towards it, nothing bad will happen,” Somar would reflect when warned of the dangers of the sea crossing.

Somar, his sisters and cousins were the first to undertake the voyage. The five of them and the boat’s navigator impossibly managed to fit into the 3.5 x 1.5 meter rubber dinghy. The journey cost them USD4200.

“I held onto Salsabil’s arm and closed my eyes. It was too dark to see anything,” Somar’s 15-year-old sister Lubna told me. “Then Salsabil started talking about the lights flickering from the island ahead and I opened my eyes. They were beautiful.” Somar, who had passed the journey rocking back and forth while reciting prayers, jumped in joy and relief when they arrived safely.

***

For the rest of the group, Al Hajj negotiated a fee of USD800 per person, on the condition that they would be transported separately with different groups of asylum seekers. He reassured them that if the dinghy was caught by Turkish coastguards, they would be able to try again after a couple of days.

As we sipped Turkish coffee, I posed Al Hajj a question that had been playing on my mind for weeks: “I understand you are offering a solution for people wanting to migrate, but why charge so much for a crossing that legally costs €25?” He explained that he would receive only 150 Turkish Liras (around USD50) per person, while the rest would be paid to the boat owner and bribes to the Turkish and Greek coastal guards. I found that hard to believe but nodded and said goodbye.

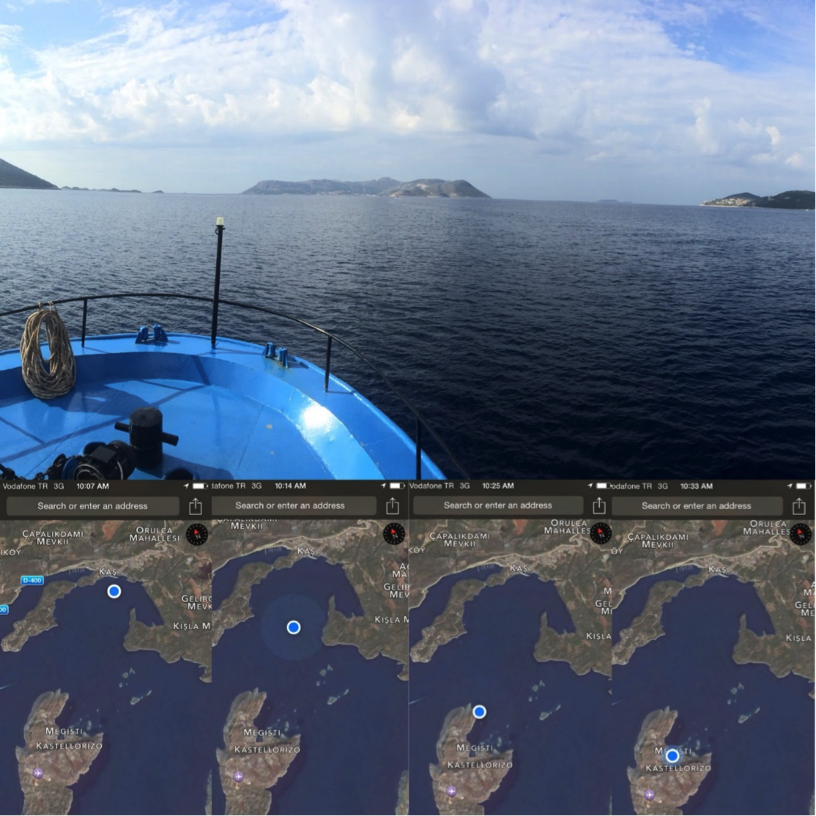

Mapping my crossing on the ferry from Kaş to Kastellorizo on google maps, 8/10/2015

The next morning, I crossed to Kastellorizo via the official ferry and met friends who had already reached the island a couple of days earlier. They guided me through thorny mountain terrain littered with discarded clothes belonging to newly arrived asylum seekers. We waited at an isolated drop off location to meet Somar that evening; the view of the Mediterranean was breathtaking.

***

As I waited for the sound of an arriving boat, my phone rang. It was Somar. He had been safely dropped off on the other end of the mountain. We managed to meet halfway, crossing through thorny bushes, and using the GPS on our phones’ and loud whistles to find each other. We led Somar and the rest of the group towards the flickering lights of the island port’s restaurants and hotels.

Our next destination was Piraeus Port in Athens. Blue Star Ferries makes the 23-hour journey twice a week from Kastellorizo. Before asylum seekers can purchase ferry tickets, which costs around €50, they must obtain a ‘service memo’ from the Hellenic police, so we remained for the next three days.

We found belongings of asylum seekers along the mountain that separated the smugglers’ drop off area from the official island port. 8/10/2015

The small island – which is home to 400 local residents - has no services in place to receive refugees. Monika Brueggebors and her husband Damien Mavrothalassitis, however, displayed exceptional generosity. They opened the outdoor area of their small, cozy restaurant to newly arrived families, offering them free meals and drinks. On Saturday, Monika crossed to Antalya to buy the travelers warm clothing and, along with some apartment owners, arranged to lend their homes for a few nights.

The habour in Kastellorizo and the Blue Star ferry that was to take us to Athens

With the worst of the journey behind them, the group was able to momentarily relax. After a good night’s sleep, they toured the little island and the men engaged in a football match with the locals, using their lifejackets as team jerseys. A few days later we boarded the Blue Star bound for Athens, high in spirit that they would soon be claiming asylum in Germany.

The football team gathers for a group photo, wearing the lifejackets as their mascots, before the start of their game. 11/10/2015. Photo credit: Alessio Mamo.

Dina Baslan is a Jordanian researcher and former aid worker. In September 2015, she accompanied her Syrian friend Somar Kreker to Europe, hiding among the refugees to nuance her understanding of the migration phenomenon first hand. This is the third in a series of articles documenting her journey, created in collaboration with the Institute's Head of Communications, Roisin Taylor.