-

What’s Inspiring WANA: “Soumission” by Michel Houellebecq

What’s Inspiring WANA: “Soumission” by Michel Houellebecq

Houellebecq’s book is about a moderate Islamic party being democratically elected in a 2022 disillusioned France. After the election, society starts slowly changing, women wear more conservative clothes, concealing their body shapes, they quit their jobs to stay home with their children, men enter polygamous marriages, and the people decide to just “submit” to Islam. Islam is not imposed by the government. It is the people who choose to embrace it.

In his review for The New York Review of Books, Mark Lilla calls Houellebecq’s creation a “dystopian conversion tale”, because what is expected to be a society characterized by human misery, as squalor, oppression, and disease, turns out to be a desirable model to live in. The Islamic model does not destroy society, on the contrary, it brings peace and relief. As a matter of fact, when we think of the end of capitalism, what usually comes to our mind are apocalyptic scenarios, such as climate catastrophes, world wars, the collapse of democracy, etc. However, we would never imagine that the European society could crush under the peaceful pressure of Islam.

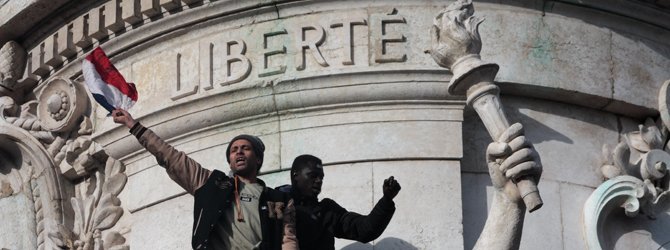

It is a dystopian conversion tale, because the author describes the return of the patriarchal model as “not so bad” after all. Sure, there may be no gender equality, no freedom and the absolute islamisation of the education system, however this new society has many valuable qualities, too: strong families, moral education, social order, a sense of place, meaningful death, and the will to persist as a culture. Islam is not the object of the author’s criticism: society is. In fact, the French (and thus European) society is portrayed as indifferent, ignoring its fundamental values and incapable of defending them. It is a logical consequence, then, that the people are happy to join a creed and get rid of their empty and purposeless freedom.

According to Houellebecq, France (Europe) has lost its sense of self, and it lost it when it placed freedom above everything else, convinced that the more it extended freedom, the happier the people would be. However, freedom can be tiring, especially in the modern world of consumerism, where freedom is just framed in terms of individual rights. It is much easier to submit to what is perceived as a “good master”, finding relief from all the capitalistic competitive stress, from the consequent humiliations, and from the more and more anguished relationship with our body.

I believe that the novel is not anti-Islam. Any religion could have been chosen, in order to portray the role that Islam plays in the story – which is that of an expanding social force, to which society, eventually, submits. The original title of the book, “Soumission”, refers both to the democratic takeover of the Islamic party, and the subsequent conversion to Islam by the protagonist, François. Islam is perhaps a luckier choice than other religions, given the recent demographic phenomena, such as the constant increase of Muslim citizens in Europe and the not indifferent number of conversions to Islam in the West (as well as the catchy pun “submission-Islam”).

This book points out that, perhaps, the world’s future and destiny are not being played on the economics field, but on the one of culture, ideas, education, and all that can leave a mark on our spiritual and mental energies, such as religion. It is worth reflecting on this point. In my opinion, education and religion do play a fundamental role. That is why the dialogue between religions is of paramount importance, now more than ever. It is also interesting to see how the novel’s moderate Islamic party, only keeps the Ministry of Education, leaving the other ministries to other parties. Education is key in building a nation. So it is perhaps useful to argue in favour of education, but aqualitative better education. It is the “how” that counts, not the “how much”.

Another interesting theme of the book is freedom. Lilla notes that the Islamic government is not interested in having freer human beings, but better ones. Society does not mind, since freedom seem a fair price to pay in exchange for a good quality of life. So what is more important, being good or being free? In my opinion, if there is no freedom, one is forced to be good, and therefore he is not. Being good means to choose to behave in a certain way. For instance, Hobbes theorised that the best form of government is an absolute monarchy, led by an enlightened monarch. In this case, there would be no freedom, and the monarch would eventually expect “submission” from the people, since most of men are nor just nor enlightened. The problem here, which is also my critic to Houellebecq, is that people are happy to submit for a while. Then they get bored of it and want to do what they want, and when they find out they cannot, they get irritated. They will look for new alternatives, and the circle starts again.

Also, arguably, in Islam there already is an enlightened and just monarch, and that is Allah. God gave us the law, because we are creatures and not creators and our freedom is Islam. The fact that Houellebecq chooses to portray a society where everyone converts to Islam as a dystopic reality does not mean that he is anti-Islam, but that he is looking at religion from an indestructible atheism. The lack of spirituality in the book, also reflects the Western society’s disinterest towards the sacred. The cartoons and films that inflame the Muslim spirits, would not have the same effects if addressed to a Christian-Western audience. Religion has been progressively abandoned in the West, after the Enlightenment. Perhaps, this is what “Soumission” is about: after we (the West) killed God (Nietzsche) and got intoxicated by that sense of power, now someone is trying to reanimate Him.