-

On The Refugee Route Part II:"My Younger Sister Barely ...

On The Refugee Route Part II:"My Younger Sister Barely Remembers Me"

After spending three years in Jordan, detached from home and family, Somar was starting to get accustomed to life as a single man with minimum responsibility. “All I worried about in Jordan was my rent, but when I saw my sisters? My God! I realised how far removed from responsibility I was,” he told me. The journey started with reestablishing a connection with his sisters. “My younger sister barely remembers me, only through pictures she tells me”, he said in disbelief. Somar was committed to changing that reality.

The second big change Somar was learning to live with was the overwhelming size of Istanbul. Coming from a village where he used to know every family, he felt so small. He even said he already felt nostalgic to the simplicity of Amman and its cozy coffee houses. As he busily navigated the metro against the minaret-embellished cityscape, acknowledging he is one of the millions using public transportation daily, he treaded along the start of what he now understood will be a long path ahead.

Coincidence had it that Somar landed in Turkey a day after an iconic image had invaded homes and hearts around the world. The waves washing over Aylan Kurdi’s stiffened body lying helplessly face down on a beach near Bodrum demoralized the humanity in all of us. It especially shook the resolve of those planning on making the same journey across the Mediterranean with family members.

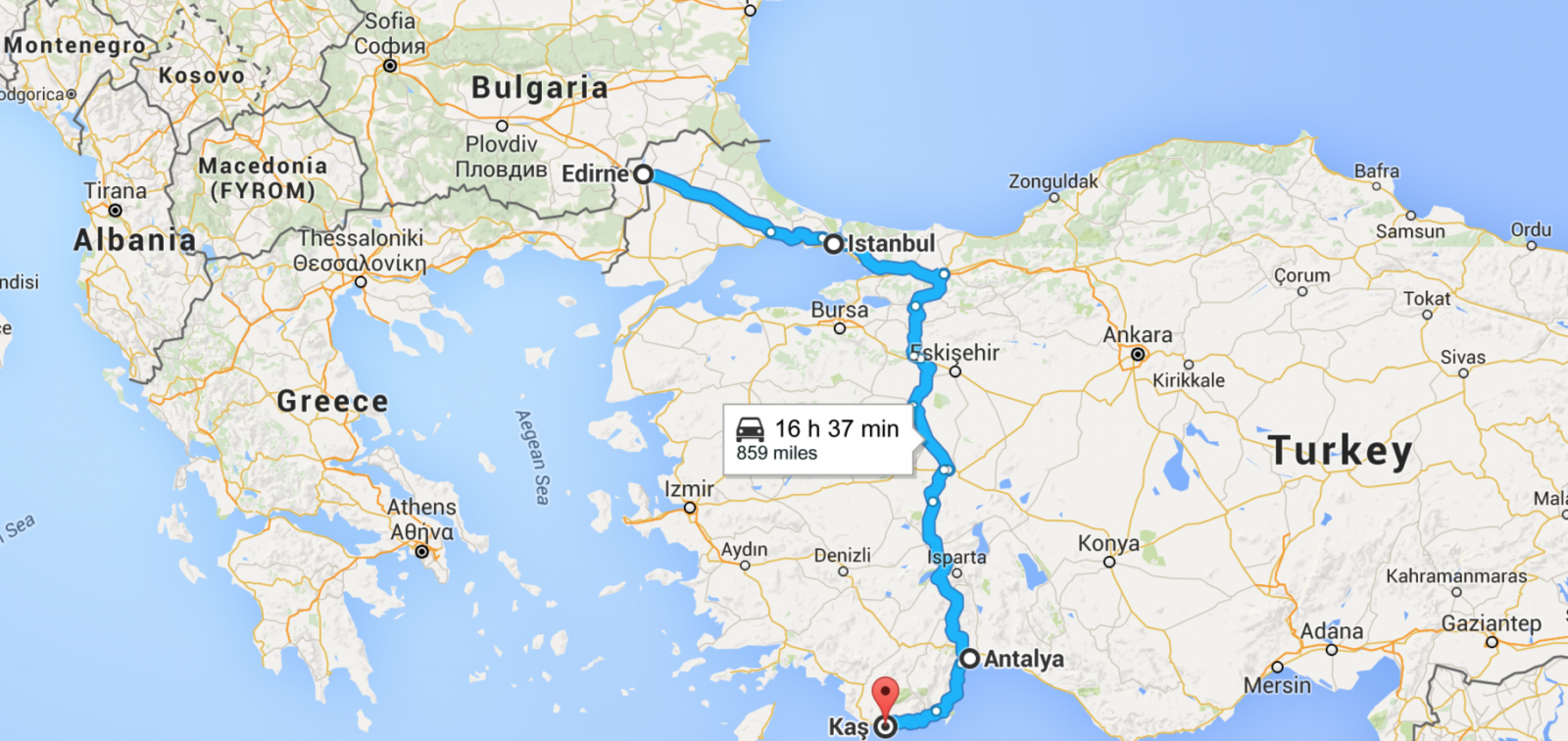

Anger and fear drove up to 3,000 Syrians to the streets of Turkey, demonstrating under the slogan “Crossing, No More” up the highway leading to Edirne, the Turkish border city with Greece. Somar and his sisters joined this group.

At the time, Turkey was incarcerating journalists for “helping and abetting refugees”, while routes to Edirne were being closely controlled in an effort to obstruct Syrians from reaching the border city. The demonstrators’ stance was of high political value for Turkey by providing a counter-narrative to Europe’s accusations that Turkey was facilitating refugees’ passage to Europe.

Demonstrators implored Turkey, Greece and the international community to open a humanitarian corridor into Greece; a solution organisations including Doctors without Borders (MSF) continue to advocate for against escalating Mediterranean deaths. According to the International Organisation for Migration, fatalities have increased over 300 percent from 2014 to 2015, reaching 279.

But just as the #SafePassage campaign continues to be ignored, so were the voices of the demonstrators. Turkey tolerated the protesters for around a week, as they moved them to a public stadium under the watchful eye of hundreds of Jandarma forces (Turkish Gendarmerie General Command). But as the week came to an end, rows of buses lined the entrance with destinations stickered on the windshields pointing to Istanbul, Izmir and Bodrum – the latter two known to be sea smuggling harbors to Greek islands. BBC investigated the detention of some of the demonstrators who were deemed “troublesome”, and revealed instances of torture and even forced deportation to Syria, a blatant breach of international humanitarian law.

At the time, Greece was the only route Somar was considering, as Bulgaria managed to garner an infamous reputation in the way it was receiving refugees, including excessive force practiced by police and xenophobic attitude from the people.

Somar looks out at of the Tunca river that runs through Bulgaria and Turkey. Stories of people getting stuck on the borders in Bulgaria deterred asylum seekers. 23.09.2015

Against these developments, Somar and his sisters decided to embark the infamous journey across the Mediterranean. We packed up and moved to the Turkish coastal city of Antalya. In discussions with young Syrians he met along the way, Somar heard of a less-trodden path through a small touristic coastal town called Kaş and across the Mediterranean to the Greek island of Kastellorizo (known as Megisti in Greek).

Nearly five kilometers of water separates Kaş from Kastellorizo. It took Somar and his friends around the hour to find a contact: a Syrian smuggler in his early thirties who referred to himself as Al Hajj (the pilgrim) and insisted that his name be saved in mobile phones as such to prevent him being tracked by authorities. He invited us to his humble home for a Syrian dinner of maqlouba (rice, chicken and eggplants) where he told stories of his young daughter who loves feeding ducks, clearly seeking our trust just as much as we were probing ourselves to trust him.

Al Hajj had been living in Kaş for little over a year. He described himself as doing his “humanitarian duty” by helping Syrian refugees reach Europe. “I am a Syrian myself and know what it means to flee a war,” he said to me. I didn’t trust Al Hajj. In my view no one with genuine humanitarian aspirations would accept to profit from an illegal and risky business. But Somar did; the two engaged in political debates about the fate of Syria for hours on end. More importantly, Somar was trusting this man with the lives of his sisters, and as he was learning to live with responsibility, he saw his relationship with Al Hajj as an investment. In retrospect, I have a feeling that Al Hajj had arrived in Turkey seeking to migrate himself, but then seized an opportunity to accumulate as much money as he could before setting sail with his family. I have since heard that he is now in Germany seeking asylum. I wondered how many other Syrians have fallen into the labyrinth of the smuggling business in the same fashion.

By that time, I was supposed to be on my way home. The plan was to assist Somar in his preparations for the journey, and then bid him and his sisters’ farewell. But I too was beyond the point of no return. Against my parents’ anxieties I forged a plan that balanced safety with insight. I would not return home, but would not ‘get smuggled’ either. Instead, I would use my American passport to purchase the €25 ferry ticket to Kastellorizo island and wait for them on the other side. And so, I found my way into continuing with the Krekers on their hard journey out of the region.

Banner photo credit: Alessio Mamo

Dina Baslan is a Jordanian researcher and former aid worker. In September 2015, she accompanied her Syrian friend Somar Kreker to Europe, hiding among the refugees to nuance her understanding of the migration phenomenon first hand. This is the second in a series of articles documenting her journey, created in collaboration with the Institute's Head of Communications, Roisin Taylor.

Route taken by Somar Kreker and his sisters from Istanbul to Erdine, and then back via Instanbul to Antalya and Kas.